This site is also available on:

Deutsch

Space debris poses a growing threat to space infrastructure. More than 400 experts from over 30 countries will gather in Bonn from April 1 to 4, 2025, to participate in the 9th European Conference on Space Debris, organized by ESA and the German Space Agency at DLR.

A global problem

Space debris is continually growing, posing a threat to hardware both in space and on Earth. The conference will address the comprehensive research area of space debris, including monitoring technologies, the growing number of active spacecraft, and the risks posed by re-entries into Earth‘s atmosphere.

Sustainable space travel

Dr. Walther Pelzer emphasizes the need for a sustainable space program to protect space infrastructure. He points to the signing of the Zero Debris Charter, an agreement initiated by 40 European space stakeholders. The goal is to minimize the risks of further space debris.

Future challenges

Conference participants will discuss the challenges posed by increased activity in space and the limitations of using Earth’s orbit. New technologies for satellite tracking and orbit determination will also be addressed to avoid collisions and ensure safety in orbit.

Environmental impacts of space travel

The German Space Agency is concerned about the increasing environmental impacts of space travel. According to Dr. Manuel Metz, the complex and urgent nature of these issues is being intensively researched, including the impact of space travel on astronomy and lunar orbits.

The German Space Agency at DLR plays a key role in international space research. By coordinating and supporting projects to prevent space debris, it contributes significantly to the sustainable use of space. The goal is to ensure the safe and long-term viable use of space.

Background info: Space debris

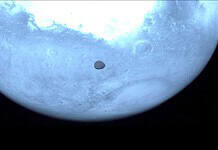

Space debris encompasses all human-made objects in Earth’s orbit that are not serving a functional purpose. Typical examples include decommissioned rocket stages and deactivated satellites, but also astronauts’ lost tools. The largest contribution comes from debris created by explosions, the breakup of spacecraft, or collisions in orbit.

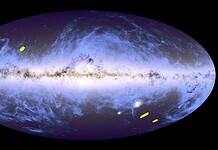

Currently, approximately 40,000 recorded and catalogued objects with a diameter of at least ten centimeters orbit the Earth. Scientists use models such as the ESA-MASTER (Meteoroid and Space Debris Terrestrial Environment Reference) model, developed in Germany, to estimate the total number of smaller particles. According to their calculations, there are approximately one million objects larger than one centimeter and around 130 million particles larger than one millimeter in Earth’s orbit.

In recent years, there has been an unprecedented growth in the number of objects in space, especially small and commercial satellites in low-Earth orbit. However, this has also led to an increase in the amount of space debris. Of the 40,000 orbiting objects that researchers are tracking, nearly 11,000 are functional spacecraft.

Even the smallest pieces of space debris, traveling in orbit at up to 28,000 kilometers per hour, can seriously damage or destroy a functional spacecraft. Pieces larger than ten centimeters cause massive damage in a collision. In the worst case, dangerous clouds of debris would be released, which could in turn trigger further catastrophic collisions in a chain reaction. In this case, parts of Earth’s orbit would no longer be usable. Such an incident, known as Kessler Syndrome, would severely restrict everyday life, as communications or navigation, for example, would be massively disrupted or even fail altogether.

With the German Experimental Surveillance and Tracking Radar (GESTRA), the Fraunhofer Institute for High Frequency Physics is developing a system for detecting and tracking space debris on behalf of the German Space Agency at DLR. The system’s data is processed at the German Space Situational Awareness Center in Uedem. In addition to research purposes, it also serves to protect satellites in orbit from impending collisions. To measure the trajectories of space objects even more precisely, the German Space Agency at DLR recently began procuring three new sensors for this purpose.